Main Page

Citizens organising solidarity across borders is nothing new. Speaking merely of recent history in Europe, we can think of workers' internationalism, feminism, the fight against fascism and totalitarianism, anti-colonialism and the struggle for racial equality among others. To this, we can add the rising awareness and activism on environmental issues, global poverty, human rights and anti-discrimination, as well as support for refugees. Also within the European Union we find many expressions of this transnational solidarity activism. On this site, we wish to present some of these initiatives in order to draw lessons from their activism and provide suggestions about the way of organising transnational solidarity more effectively. While citizens encounter several impediments in organising across borders and in influencing the direction of events, we should not conclude that such attempts are futile, even utopian. The EU-funded TransSOL project has provided systematic data on citizen engagement in support of transnational solidarity in several fields of activity (unemployment, disability, and migration/asylum), and has thus evidenced that hundreds of citizens' groups and organisations are committed to struggling for deprived groups, advocating for their rights and working towards social and political changes. In particular, we have taken a closer look at exemplary cases of citizens’ initiatives effectively engaged in organising transnational solidarity. This has allowed us to identify lessons about good practice and paths towards improved activism. In particular, we have looked at the experience of the Transnational Social Strike in their attempt to organise workers transnationally in the gig economy; we have looked at the initiatives, run by several European municipalities, to develop transnational networks to welcome migrants; and, finally, we have looked at the development of Krytyka Polityczna, a cultural and social NGO operating across Eastern Europe. Additionally, we spoke with several initiatives, whose testimonies we include in video material.

Contents

What seems to work best when organising solidarity transnationally

- Transnational symbols are powerful and build solidarity: more and more people are aware of how crucial political issues cross borders are but feel powerless. Even small initiatives across borders that show some success can generate lots of enthusiasm for this reason.

- Think about your interlocutor: who are you asking for what?: an effective advocacy campaign needs to identify who it wants to act and its exact demands. Very often, an issue is transnational because multiple authorities need to act.

- Act locally in a network across countries: Most likely other people across Europe are already concerned about the issue you are concerned with, and may already be active. Look, learn and connect with them and quickly you'll have a transnational network.

- Keep formal organisation to a minimum, but work to build new institutions over time! Creating a formalised organisation too quickly creates overheads and personnel issues which might not be necessary at that stage, and too often maintaining organisations becomes an end in itself. Instead of thinking of a new organisation, it is often better to think of a new institution or way of existing actors working together, taking decisions together and relating with authorities.

- Reach out to different ages! Solidarity also needs to be expressed between ages, and modes of organisation of campaigns often shut out otherwise enthusiastic participants (whether they are older and less active on the Internet, for example, or have caring responsibilities which make some forms of activism more difficult)

- Don't talk about, talk with! Nothing undermines a campaign more than not giving voice to the people it claims to represent. So that your activism does not become part of the problem rather than the solution, you have to think about how it empowers others and establishes new solidarities.

- Translation is a crucial tool - turn diversity to your advantage! Instead of seeing many languages as a disadvantage, see it as a resource: content that can be translated, ideas that can be spread and natural curiosity about others that can be brought into the activism. Translation can turn your activism into a rich process of learning as well as political change-making.

- Digital and physical meetings must go together and be sustained! It is all too easy to think that the Internet solves our problems, when in creates as many barriers as it breaks down. Physical meetings are indispensible for real understanding, building trust and long-lasting relationships.

- Regional specificity can be a starting point for further expansion! Instead of aiming to be active across Europe immediately, it can be an idea to start bringing together contexts with similar historical experiences, cultures or languages, and use that strong base to develop further.

- Long-term partnerships across countries can yield the best results - invest in them! Getting organisations to work together requires patience and compromise, but over the long run the benefits are often much more than could be imagined at the beginning: In a changing and complex political landscape, there are always new reasons for mutual support, solidarity and common action.

- Use all the possibilities already opened up by the EU to build transnational networks and actions: freedom of movement, ease of setting up associations, funding and the different legal avenues opened up by the EU all provide significant and underused advantages for civil society acting across borders.

Interviews

Baobab—We do not know what happens tomorrow: Since May 2015 a group of volunteers have faced a migratory emergency handling more than 35,000 transit migrants in the city of Rome. Today they continue to give a first welcome on the street, supported by medical and legal associations and by the network established with national and European human rights activists. |

|

Against the angst — Shelter Cities: Barcelona stated: “We are actually willing to take in people looking for shelter—above all people seeking protection from the Syrian War” Then, little by little, other cities join the call, started in Barcelona. Today (2018), almost three years later, a program called Shelter Cities exists. | |

The “ecosystem” Social Solidarity: Solidarity in Europe is one of Christos Giovanopoulos’ main concerns. Although there is no patent remedy, his work in solidarity movements shows, that developing solidarity is a combination of factors, to which people will resort when realising, that they can count on each other for support. The creation of spaces for social participation is the main prerequisite so that people can succeed on society solidarity. |

Either rise or fall together: The Transnational Social Strike (TSS) Platform aims at competing kinds of workers, men and women, immigrant workers … and tries to lead them to solidarity with the others, because: “To be in solidarity with the others is at the same time to be in solidarity with yourself.” |

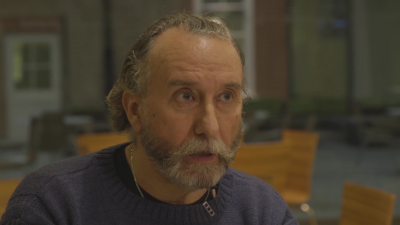

Without Solidarity—no Democracy : This knows Greg Thomson, official of UNISON—the second largest trade union in the United Kingdom with almost 1.3 million members—, who deals with workers, who are migrant workers, on the basis of their being EU citizens. Democracy itself does not work, democracy goes hand in hand with solidarity because unless you are prepared to treat all human beings being of value and honestly and sincerely respect them and treat them with dignity, then you do not have a society that is worth living in. |

All solid melts into air: This dictum of Karl Marx is one of the important maxims for Vasyl Cherepanyn, who is Head of the Visual Culture Research Center, Lecturer at the Cultural Studies Department of the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, and Program director of The Kyiv International – Kyiv Biennial 2017. http://vcrc.org.ua/en/people/] |

Best Practices

| How should transnational activism be organised? |

|---|

| For the experience of Krytyka Polityczna, there are general lessons to be drawn regarding the internal organisation of a civil society organisation.

First of all, translation should be seen as a vital political tool. As Krytyka Polityczna demonstrates, polyglot communication can facilitate much more than just the sharing of neutral information in new contexts. If framed effectively, translated materials actively build cultural spaces, and forms of cultural cooperation. Secondly, the use of digital and social media, as well as other pan-European infrastructures, can enable communities to develop both in concentrated moments (such as real-life events) and prolonged communication (online groups). The two, however, need to be held together. Democracy 4.0 is a good example in which several real life meetings were organised to reflect on the digital tools themselves. The lessons learnt resulted in precisely those tools being used to create further action on the street, in squares and other public spaces, as well as for reinventing AGORA. Digital technologies, we might conclude, only bring solidarity when they facilitate new political meeting points. Further, regional specificity can act as a spring-board for larger scale solidarities. One of the reasons why Krytyka Polityczna’s pan-European initiatives have been so successful is that they were conceived in gradual terms. They began with an emphasis on the Visegrad region and developed into something larger in scale. Even in processes of transnational communication, then, local and national experiences continue to be grounding forces. In addition, our cases show that specific long-term partnerships yield the most fruitful results. The case of the Ukrainian partnership demonstrates how years of prolonged communication and community building are essential to building effective transnational structures. When the dual national institution was founded in 2010, participants were not aware of the various turning points that would come in the following years and how mutually beneficial the structure would prove to be. With this community already in place when shots started, however, they were ready to respond to unexpected challenges rising from the conflict with a sustainable institution that was resilient to the unfolding events. Finally, it is important to point out that solidarity is already being facilitated by the EU itself. Leaving aside criticisms of specific institutions, Krytyka Polityczna’s activities are a good example of how the EU remains a space with certain novel privileges for organisations working to build forms of solidarity beyond national and class-based communities. That such an innovative form of cultural activism has taken root in Poland against precisely such nationalistic and oligarchical forms of opposition, is testament to the democratic value of this pre-existing transnational political space. Freedom of movement and speech are today under assault from all sides, but the forms of solidarity pioneered by civil society actors across the EU demonstrate how much groundwork has already been done to defend and redefine these terms for the future. |

| How can cooperation and momentum be generated between organisations and their activists? |

|---|

| The case of the transnational strike reveals the important role of the media in building momentum. Social media provides a powerful tool, facilitating connections, at the communicative level, between actors that experience difficulties in coordinating their struggles. One might say that the same digital technologies used to exploit workers are then used to organise the struggle against exploitation. Nevertheless, it is true that the strategic construction of a feeling of shared belonging, of identifying as part of a growing movement, is a crucial aid for civil society organisations.

Furthermore, effective local collectives engaged in labour struggles seem to be substantially based on pre-existing activist networks with politicised activists inside workers’ collectives acting as brokers in the transnational sphere. In general, the construction of concrete mechanisms of coordination of struggles between different countries is yet to come. Most activists are primarily focused on building their local struggle, accumulating strength, recruiting riders, and so on. Overcoming many of their challenges, however, would require a rethinking of EU funding mechanisms and legislative agendas. On the one hand, the resources to be dedicated to transnational connections are rather limited and, on the other hand, it is difficult to build a common transnational agenda when legislative contexts are different from each other. Workers and activists deeply feel the need to broaden the scope of their struggle so as to reach the same transnational level on which companies are placed. In the same vein, researchers point out that bringing the struggle to a transnational level may be much more fruitful than waiting for an intervention by policy-makers. |

| How can cooperation and momentum be generated between civil society and state actors? |

|---|

| What becomes clear through analysing the Cities of Solidarity is that there must be a structural reform of the European and national regulatory framework, which foresees a modification of the current international Conventions on the right of asylum and a more supportive migration policy, sharing responsibilities and burdens on a transnational level. The European Commission and European Council should give political and financial recognition to the role of cities, and local authorities should have the broadest political and financial autonomy in migration matters granted to single national governments. The construction of stable and developed transnational networks between cities is necessary, providing for the strengthening of exchanges of good practices and models of reception and social inclusion, the possibility of negotiating with one voice in front of European institutions and national governments, and the possibility of developing autonomous city-to-city policies, bypassing the direct control of nation-states. |

Further Reading

A lively debate and practice exists around transnational solidarity and activism that cross borders. For an academic overview, as well as in-depth versions of the case-studies we have touched on above, see the research outcomes of the European research project TransSOL: Transnational Solidarity in Times of Crisis [1]:

Report discussing the socio-economic, political, legal, and institutional context of transnational solidarity – the position and role of solidarity in legal systems of the eight TransSOL countries as well as legal and policy consequences of the crisis.

Report summarising the findings of an analysis of innovative practices of transnational solidarity in response to the crisis, focusing on citizens’ initiatives and networks of cooperation among civil society actors.

Report on the results of a large-scale representative survey, targeting individual attitudes and behaviour regarding solidarity.

Report targeting civil society organisations and their (trans)national organisation of solidarity in times of crisis.

Report summarising the findings of an analysis of claims in newspapers and Facebook comments regarding solidarity with refugees during the crisis.

The pilot study looking at three cases of solidarity in practice, on which this guide builds.

Several texts have been produced by the main actors of transnational actions and practices themselves. Among them, we recommend the following:

- Early on, after the onset of the economic crisis, economists were already arguing that Europe’s response was not right, see Manifesto of the Appalled Economists.

- A good summary of civil society proposals to address the economic crisis can be found in the ISIGrowth report How can Europe change?.

- The Citizens Manifesto brings together proposals for European reform devised through a participatory process of 80 citizens’ assemblies across Europe.

- The Charter of Lampedusa brought together hundreds of NGOs and social movements to craft an alternative European migration policy.

- For an inspirational example of migrants and artists jointly articulating a new global condition, see the Migrant Movement Manifesto.

- For an attempt at bottom-up transnational labour coordination, see the Transnational Strike Platform.

- There have been several attempts to rejuvenate political alternatives at the transnational level. Among them, the pan-European movement DiEM25 was launched in early 2016 with a manifesto for change.

- For an attempt to bring together social movements and left-wing forces in Eastern Europe, see the Democratic Left 18 Manifesto.

- For an overview of Europe’s new municipalist movement, rich with links for further reading, see Beppe Caccia’s introduction to Europe’s New Municipalism.