Main Page

TransSOL Wiki on Good Practices

What motivates people to engage in transnational solidarity?

Transnational Civil Society Solidarity Initiatives

Contents

Best Practices

1 Inner organization: How should transnational activism be organised?

3 How can cooperation and momentum be generated between civil society and state actors?

4 Good Practices: A Public Forum

Three Cases of Effective Transnational Activism

What lessons can we learn from analysing activist organisations that have already proven to been effective? How are these networks organised? What are some of the challenges they face?

The TransSOL Project, and in particular the transnational civil society organisation European Alternatives, researched the goals, platforms, organisation, effectiveness and challenges faced by three networks that have been able to facilitate solidarity across European nations. These organisations have a lot to teach us on what works for getting people together at a grass-roots level, and for cooperating with shared aims having to do with migration, disability and employment.

Who are these organisations? What do they do?

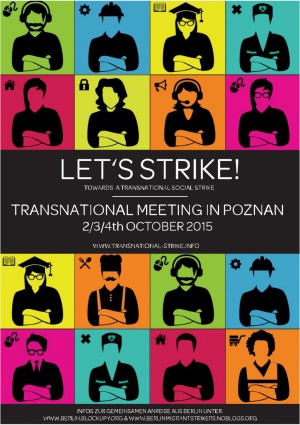

The Transnational Social Strike began in 2014 with the aim of linking diverse movements of precarious workers, migrants and the unemployed. Rather than an institution like a trade union, it is a network of communication for the exchange of knowledge and tactics across borders. In particular, it addresses the question of how to withhold labour as a form of effective activism. The group holds regular international meetings and publishes material in several European languages.

In the past two decades, labour has become both more flexible and more precarious. The introduction of online platforms in the labour market in the last few years have reshaped and accelerated these processes, giving birth to the so-called ‘gig economy’, a system in which working activities are completed through a series of tasks facilitated by online platforms. The food delivery industry is the sector which has the most significant cases of organisation. Young adults riding on bicycles while carrying boxes marked by the logos of companies like Foodora, Deliveroo, Justeat, Glovo, and so on, are a common sight in most European cities. Customers order food from a restaurant of their choice through a website or an app, and riders deliver it as quickly as possible. Their forms of employment tend to vary significantly across countries and companies as well as the way is which they are paid. What they have in common is the fact that they are not considered to be regular employees of the food delivery platforms, but instead free-lance workers that perform a series of ‘gig’, thanks to the service provided by platforms.

The Transnational Social Strike has increased its activities in the past few years. The Transnational Food Platform Strike Map built by French activists shows three protest events for 2016: the protest in front of the Deliveroo headquarters in London in August, the strike of Foodora rider in Turin in October, and the protest of Deliveroo rider in Bordeaux in December. For the following year, 2017, the same map reports 40 protest events, in 8 different countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Spain and the United Kingdom). This group is gaining in momentum, and linking activists across European countries.

What European Alternatives researchers have called Cities of Solidarity confronts the limitations of migration policies put in place by single national governments. Civil society has been organising in innovative ways, with numerous associations and networking experiences springing up all across the continent. These organisations focus on migrant reception, education and placement in the labour market as well as facilitate social integration processes. These initiatives meet, in a significant number of cases, with a willingness to cooperate on the part of local and municipal authorities.

These organisations have required the cooperation between self-organised migrant groups, informal associations and structured NGOs, on the one hand, and City governments on the other. At the same time, such cooperation has fostered new transnational networks, with relationships and connections built between single cities, with the aim of presenting shared proposals for asylum and migration policy and coordinating practical efforts in solving daily and long-term problems in the reception and social inclusion of migrants.

Krytyka Polityczna is a Warsaw-based civil society organisation engaged in transdisciplinary activity spanning Central and Eastern Europe and Ukraine. The organisation is involved in several initiatives, the centre of which is a journal and independent news platform. In addition, the network runs a publishing house while managing over 20 social clubs across the country. The organisation is a good example of ‘horizontal’ or geographical solidarity among and between the V4 countries and beyond, but also shows vertical political solidarity with local grassroots initiatives, bridging the divide between intellectuals and the public.

Krytyka Polityczna’s efficacy as a model is best demonstrated by its capacity to maintain cross border initiatives like these over a long period, to develop intellectual ideas not only in short individual projects but over several years at a global level and, just as importantly, at a level well-defined politically within Europe.

Why are these organisations effective at promoting European solidarity?

When TransSOL researchers looked into reasons people join CSOs (civil society organisations) in the fourth work package, the team received answers which confirm the notion that there is in fact already solidarity across Europe. Our exemplary cases of these three networks reflect a motivation to join based on both personal and political interests. But motivation is not enough: organisation matters. Lessons learned from the three case studies provide insights on the way activism should tap into the motivation in order to momote longer-term coorperation across European countries.

How should transnational activism be organised?

For the experience of Krytyka Polityczna, there are general lessons to be drawn regarding the internal organisation of civil society organisation. First of all, translation should be seen as a vital political tool. As Krytyka Polityczna demonstrates, polyglot communication can facilitate much more than just the sharing of neutral information in new contexts. If framed effectively, translated materials actively build cultural spaces, and forms of cultural cooperation.

Secondly, the use of digital and social media as well as other pan-European infrastructures can enable communities to develop both in concentrated moments (such as real-life events) and prolonged communication (online groups). The two, however, need to be held together. Democracy 4.0 is a good example, in which several real-life meetings were organised to reflect upon the digital tools themselves. A combination of both led to further actions in streets, squares and other public spaces. Digital technologies, we might conclude, only bring solidarity when they facilitate new political meeting points.

Further, regional specificity can act as a spring-board for larger-scale solidarity. One of the reasons that Krytyka Polityczna’s pan-European initiatives have been so successful is that they were conceived in gradual terms. They began with an emphasis on the Visegrad region and developed into something larger.

In addition, this case shows that specific long-term partnerships yield the most fruitful results. Partnership with Ukraine demonstrates how years of prolonged communication and community-building are essential for sustaining effective transnational structures. When the dual-nation institution was founded in 2010, participants were not aware of the various turning points that would come in the following years and how mutually beneficial the structure would prove to be. With this community already in place, however, they were ready to respond to unexpected challenges of new conflicts with a sustainable institution that was resilient to the unfolding events.

Finally, it is important to point out that solidarity is already being facilitated by the EU itself. Krytyka Polityczna’s activities are a good example of how the EU remains a space with certain novel privileges for organisations working to build forms of solidarity beyond national and class based communities. That such an innovative form of cultural activism has taken root in Poland, against precisely such nationalist and oligarchic forms of opposition, is testament the democratic value of this already existing transnational political space. Freedom of movement and speech are today under assault from all sides, but the forms of solidarity pioneered by civil society actors across the EU demonstrate how much groundwork has already been made in defending and redefining these terms for the future.

How can cooperation and momentum be generated between organisations and their activists?

The case of the transnational strike reveals the important role of the media for building momentum. Social media provides a powerful tool, facilitating connections at the communicative level between actors that experience difficulties in coordinating their struggles. One might say that the same digital technologies that are used to exploit workers are then used to organise the struggle against exploitation. Nevertheless, it is true that the strategic construction of a feeling of shared belonging, of identifying as part of a growing movement, is a crucial aid for civil society organisations.

Furthermore, effective local collectives engaged in labour struggles seem to be substantially based on pre-existing activist networks with politicised activists inside workers’ collectives acting as brokers in the transnational sphere.

In general, the construction of concrete mechanisms of coordination of struggles between different countries is yet to come. Most activists are primarily focused on building their local struggle, accumulating strength, recruiting riders, and so on. Overcoming many of their challenges, however, would require a rethinking of EU funding mechanisms and legislative agendas. On the one hand, the resources to be dedicated to transnational connections are rather limited and, on the other hand, it is rather difficult to build a common transnational agenda when legislative contexts are different from each other. Workers and activists deeply feel the need to broaden the scope of their struggle as to reach the same transnational level on which companies are placed. In the same vein, researchers point out how bringing the struggle to the transnational level may be much more fruitful than waiting for an intervention by policy-makers.

How can cooperation and momentum be generated between civil society and state actors?

What becomes clear through analysing the Cities of Solidarity is that there must be a structural reform of the European and national regulatory framework, which foresees a modification of the current international Conventions on the right of asylum and a more supportive migration policy, sharing responsibilities and burdens on a transnational level. The European Commission and European Council should give political and financial recognition of the role of cities, and local authorities should have of the broadest political and financial autonomy in migration matters granted to single national governments. The construction of stable and developed transnational networks between cities is necessary, which provides for the strengthening of exchanges of good practices and models of reception and social inclusion, the possibility of negotiating with one voice in front of the European institutions and national governments and the possibility of developing autonomous city-to-city policies, bypassing the direct control of the nation-state.

The full report can be found at www.transsol.eu[4]

Recent Events

Sustaining Solidarity in Europe

In collaboration with SOLIDUS, the TransSOL team hosted Sustaining Solidarity in Europe on 15 May 2018 in Brussels at the Factory Forty venue. The public event brought together social scientists, NGO/CSO representatives and members of the public in order to collectively address the factors that promote or discourage transnational colloaboration across European countries.

Discussion began at 9am and ended at 6pm, and TransSOL researchers Christian Lahusen, Simone Baglioni and Maria Kousis made important contributions to the public dialogue.

European Solidary: Conditions, Forms, Limitations and Implications

The TransSOL Project held its final event on 16-17 May 2018 in Brussels at the Factory Forty venue. The conference, which included TransSOL researchers and guests, featured a presentation and discussion of the past three years of research findings.

Guest keynote speakers included Gian-Andrea Monsch (University of Lausanne), Caroline de la Porte (Copenhagen Business School) and Maria Petmesidou (Democritus University). In addition to TransSOL topics such as civil society, public opinion and public discourses on solidarity, participants also had the chance to discuss the concept of the common good, welfare reform and austerity and the implications of neoliberalism for public policy.

About TransSOL

TransSOL is an EU-funded research project dedicated to describing and analysing solidarity initiatives and practices at a time in which Europe’s existence is challenged by the consequences of the 2008 economic and financial crisis, by the problematic management of large fluxes of refugees and by the outcome of the 2017 Brexit referendum. In particular, TransSOL focuses on three areas of vulnerability: migration, unemployment and disability.

Consortium

European Alternatives[5] https://vimeo.com/269581909

Glasgow Caledonian University Yunus Centre for Social Business and Health

University of Copenhagen Department of Media, Cognition and Communication

University of Crete Department of Sociology

University of Florence Department of Legal Sciences

University of Geneva Institute of Citizenship Studies

University of Sheffield

Department of Politics

University of Siegen Centre for Research in the Social Sciences

University of Warsaw Institute of Social Policy

Sciences Po Paris Centre for Political Research

Web

www.transsol.eu[6] Twitter: @TransSOLproject[7] Facebook: TransSOLproject[8]